John Marshall, the Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India from 1902 to 1928, published his report on the findings from the excavations at Mohenjo Daro in 1931. However, Marshall neither discovered Mohenjo Daro nor was he the first to excavate there.

Rakhal Das Banerji (also known as Rakhal Das Bandopadhyay) discovered Mohenjo Daro in 1921. He was the Superintendent of the Western Circle for the Archaeological Survey of India at that time. Banerji, along with Daya Ram Sahni, was the first to excavate and unearth the remains of the once magnificent city of Mohenjo Daro in 1922; Marshall and his team excavated much later, in 1925.

Banerji submitted a report to Marshall in 1926 on his excavations and findings at Mohenjo Daro for publication by the Department of Archaeology, Government of India.

However, the report never saw the light of day.

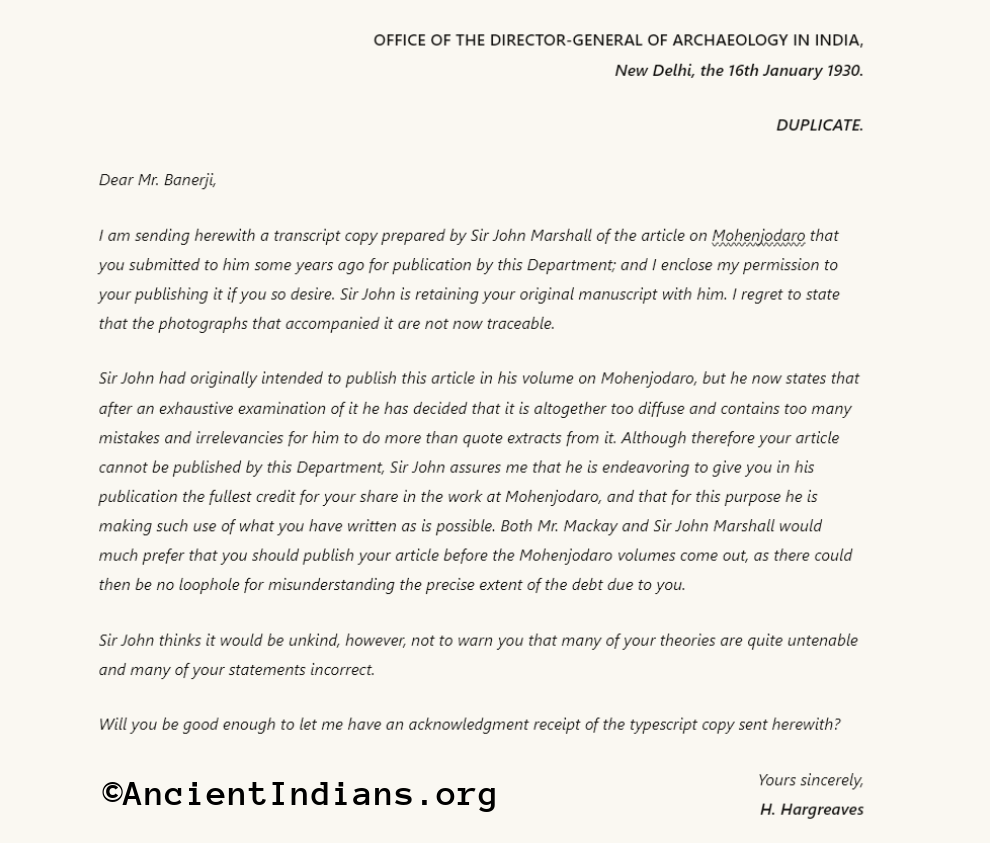

Four years later, in 1930, Banerji received a typed copy of the report accompanied by a letter informing him that his report could not be published, and he was free to publish it separately. Marshall kept the complete original report, including the photos and illustrations, and, in 1931, published his own report.

Incorrect, Irrelevant, and Untenable.

Marshall described Banerji’s report as ‘Incorrect, Irrelevant, and Untenable,’ according to a letter by Harold Hargreaves, the Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India from 1928 to 1931. A full reproduction of the letter received by Banerji from Hargreaves is presented below.

Despite Banerji’s repeated requests for the return of his original report, he received no response. Given the scarcity of printing facilities at the time, Banerji lost valuable time in the process, and meanwhile, Marshall published his own volume on Mohenjo Daro

The Conspiracy

After four years, when Marshall was close to publishing his own volumes on the subject, did he decide to return Banerji’s report, retaining the original, and claiming the photographs were untraceable.

Interestingly, 1926 was also the year Banerji took ‘voluntary retirement’ from the ASI.

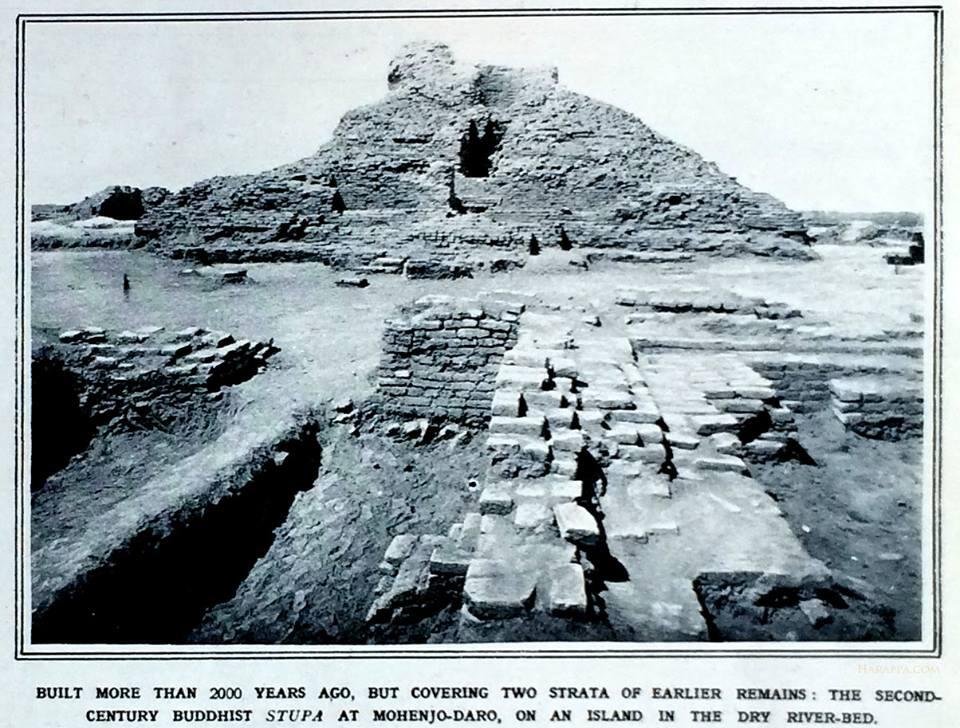

In 1924, a British newspaper, The Illustrated London News, broke the news of Mohenjo Daro’s discovery, largely crediting Marshall while merely acknowledging Banerji as the excavator. Notably, the article described the Buddhist Stupa as being located on an island in a dry riverbed—exactly what Banerji claimed in his report, which Marshall had denied. This suggests Banerji must have submitted an earlier report on his 1922 excavations, prior to the 1926 one. That earlier report likely formed the basis of the British newspaper’s article.

It is not just the report submitted in 1926; the British-led Archaeological Survey of India did not publish any reports submitted by Banerji on his excavations at Mohenjo Daro.

In his book, Rakhal Das Banerji: The Forgotten Archaeologist, author P.K. Mishra reveals that Banerji wrote to Suniti Kumar Chatterji, expressing his helplessness at being barred from publishing anything on Mohenjo Daro by the British.

“See, they (the British Government) will not allow me to publish anything on Mohenjo-Daro. But you can write something. I am handing over to you all the material I have and all the photographs. You just write something on it and publish my interpretations. This may be a record for future generations.“

Mishra, P.K. (2019). Rakhal Das Banerji: The Forgotten Archaeologist. New Delhi: National Book Trust.

However, it seemed unlikely that Chatterji would risk punishment by publishing material barred by the British Government. Therefore, if Banerji did make such an appeal to Chatterji, the latter probably did not act on it since there is no evidence he published anything on Mohenjo Daro.

The Forgotten Report on Mohenjo Daro

Marshall’s volumes on Mohenjo Daro, published in 1931, became the foundation material for understanding the ancient site. His interpretations and perspectives influenced historians, scholars, and archaeologists worldwide for many decades, shaping the narrative on the findings.

What about Banerji’s interpretations?

Between 1917 and 1920, Banerji explored the villages around Mohenjo Daro, gathering information from locals while relying on walking and carts for travel. His sociable nature helped him uncover crucial details about ancient mounds. The excavation of the stupa and surrounding areas during 1922-23 was largely conducted by Banerji and his team.

From 1918 to 1922, Banerji also surveyed the dried-up channels of the Sutlej and Indus rivers, identifying ancient riverbeds and the remains of numerous towns. He identified 17 ancient beds of the Indus and the remains of 27 major towns and 53 smaller ones.

His research led him to believe that 5,000 years ago, Mohenjo Daro was situated along an ancient Indus riverbank, with islands in the city used for temples and shrines. This is exactly what he documented in his report, which was ultimately dismissed by Marshall as “incorrect, irrelevant, and untenable.”

Banerji proposed that the stupa site once housed an Indus-period shrine built on an island to protect it from floods. He noted that the stupa and its platform were later additions, suggesting the platform originally supported an older structure. Additionally, Banerji identified rooms around the quadrangle as shrines, not living quarters, emphasizing the site’s spiritual importance.

He drew comparisons to other island-based shrines in Sindh, such as Khwaja Khizr, Sadh Belo, and Satiyan Jo Asthan—all situated on islands near Mohenjo Daro—proposing a continuity in an ancient tradition of building shrines on islands.

Conclusion

Banerji’s experience highlights the challenges faced by Indian archaeologists under British rule, where their contributions were often overshadowed or ignored.

Marshall’s dismissive characterization of Banerji’s report on Mohenjo Daro as “incorrect, irrelevant, and untenable” likely stemmed from both a personal and professional desire to uphold the authority of his own interpretations, especially regarding the Buddhist Stupa, which many scholars today question due to a lack of supporting evidence. It seems Marshall sought to establish a particular understanding of the site in the context of the British colonial narrative.

The suppression of Banerji’s work not only hindered the recognition of his contributions but also limited the understanding of Mohenjo Daro itself, as his insights provided valuable context and depth about the possible topography of the site 5000 years ago. Banerji’s interpretations in his forgotten report on Mohenjo Daro could have added more variety to the discourse surrounding the city.

Sources:

Banerji, R. D. (1984). Mohenjo Daro: A Forgotten Report. Prithvi Prakashan.

Mishra, P.K. (2019). Rakhal Das Banerji: The Forgotten Archaeologist. New Delhi: National Book Trust.

Thank you for this insightful and well-researched article. It offers valuable perspectives on our shared heritage and cultural legacy. As someone working on promoting historical awareness through my own platform, I truly appreciate the effort and depth presented here.

If appropriate, I would be honored to have my educational website https://bahawalpur.org, which focuses on the cultural, historical, and archaeological richness of Pakistan (including regions like Bahawalpur and sites such as Mohenjo-Daro), considered for inclusion as a resource or reference.

Keep up the excellent work!

Warm regards,

Dr. Aamir Raza

Founder, Bahawalpur.org