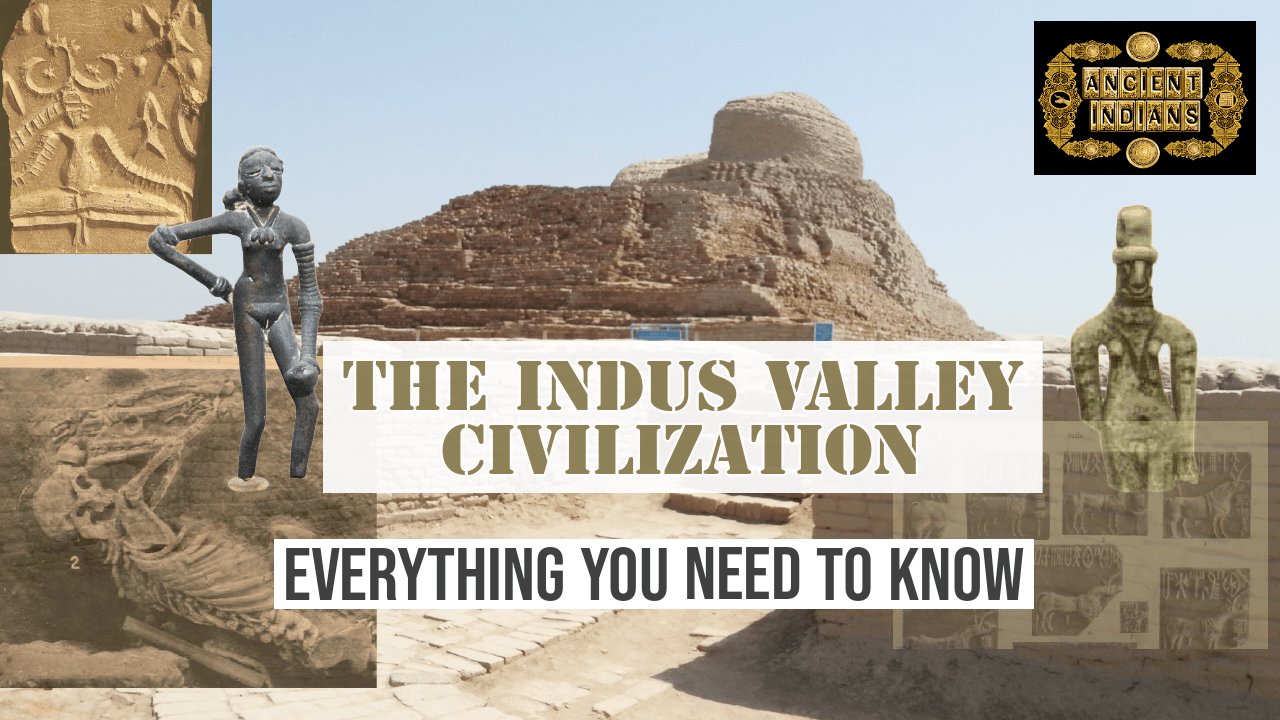

When all of Mohenjo Daro was covered under layers and layers of soil, the tip of this mound stuck out, visible even from miles away, as if trying to catch the attention of people and tell them the story of the once-great ancient city that it towered above.

Although the existence of this mound had been known for quite some time, the British were not particularly interested in excavating it because they believed it was what it looked like — a Buddhist Stupa that belonged to the Kushan or Mauryan era.

The British had just excavated Harappa, and at that time, they were only focused on discovering and excavating prehistoric sites in India. A Kushan-era Buddhist Stupa hardly warranted an urgency to be excavated.

However, in 1922, Rakhal Das Banerjee, an officer of the Archaeological Survey of India, who had already surveyed Mohenjo Daro in the year 1919, proceeded to excavate the area with the purpose to uncover and expose the Buddhist Stupa. But as he began to do so, Banerjee discovered several seals — seals that bore a striking resemblance to the Harappan seals that had been known to belong to the Chalcolithic age. The antiquity of Mohenjo Daro thus came to light, and Banerjee wasted no time in carrying out further excavations all around the site.

Had it not been for this mound, it’s quite possible that the discovery of Mohenjo Daro might have been stalled for years.

The monument beneath the mound has remained a mystery since 1922. Although it was classified as a Buddhist stupa and monastery complex from the Kushan era by the British-led Archaeological Survey of India, contemporary scholars disagree and assert that a careful re-examination is necessary to determine the monument’s exact nature and origins.

A Buddhist Stupa

The Positioning of the Stupa

The Stupa is not perfectly symmetrical in relation to the quadrangle around it. Marshall claimed this is likely because it was the first structure built by the Buddhists on this site, and the courtyard and monastery had to be adjusted to fit within the limited space on the mound. The distance between the Stupa platform and the surrounding cells varies: about 22.5 feet on the north, 20 feet on the south, 12-14 feet on the west, and 34 feet on the east.

The Smooth and Polished Interior of the Drum

The dome of the Buddhist stupa at Mohenjo-Daro had long vanished, leaving behind a hollow circular drum. It is said that villagers once dug through the middle of this drum in search of treasure and discovered a relic casket. Though remnants of this casket were uncovered during Banerjee’s excavation, there was not enough left to reconstruct it. The circular drum was constructed with sun-dried bricks and measured 33 feet and 6 inches in diameter.

Banerjee and his assistant, Mr. Wartekar, were intrigued by the precision with which the sun-dried bricks were placed, noting the smooth and polished finish of the interior. They also uncovered fragments of painted plaster, suggesting that the inside of the drum had once been decorated. However, this observation conflicted with the conventional structure of a Buddhist stupa, which typically featured a solid core of debris covered by a dome, not a hollow chamber.

To understand the importance of these observations, it’s essential to clarify that traditional Buddhist stupas were never hollow structures. Their cores were usually packed with materials such as bricks, mud, and rocks, serving the purpose of safeguarding sacred relics associated with the Buddha or other significant Buddhist figures. The solid construction was intended to preserve and protect these relics within the stupa.

When John Marshall arrived at Mohenjo-Daro in 1924, his interpretation differed from Banerjee’s findings. Marshall asserted that the drum could not have been hollow, as it was not the custom for Buddhist stupas to have internal chambers, let alone those decorated with murals. Additionally, he argued that a dome constructed with sun-dried bricks would not have been stable enough to span such a wide chamber. Furthermore, he suggested that the painted plaster fragments discovered by Wartekar likely came from elsewhere, not from inside the drum.

Yet, even Marshall conceded that the smooth finish on the interior walls of the drum was unusual, especially if it had been intended merely as a debris-filled core. He could offer no clear explanation for this anomaly.

It should be noted that the remaining Indus remains in the stupa area during the 1925-26 excavation season, after R.D. Banerjee and his team had already excavated much of it, were excavated by Mr. B.L. Dhama under Marshall’s supervision. Uncovering the prehistoric Indus remains beneath the Buddhist pavements would have required dismantling the ‘Buddhist’ structures above them, which faced significant objections. As a result, the site was never fully excavated.

The Monks Quarters

Surrounding the stupa was a courtyard lined with cells and apartment buildings, forming what Marshall identified as a Buddhist monastery—an atypical layout since monasteries are not usually built around a stupa. The complex included two assembly halls, a shrine, a bathroom, 15 monk cells on the ground floor, and possibly 25 more on the first floor, housing around 40 monks in total according to Marshall.

Each monk cell had two parts: one for sleeping and one for living, although some were too small for anything beyond sleeping.

Marshall noted four rooms behind the living quarters that he believed were later additions, possibly kitchens or storerooms, though such facilities were uncommon during the early Kushan period. He states a Monk generally begged for food in the towns, or prepared it for himself in his cell. It was much later that the monasteries developed common kitchens, pantries, and store rooms. Marshall therefore concluded that those 4 rooms were not part of the original monastery.

Large Number of Indus Burial Pots in the Monks Quarters

In Chamber 22, Banerjee found a number of pots with pointed ends, which he identified as burial urns. Marshall, however, claimed they were almost certainly drinking goblets from the Indus times. Many of these pots in the lower layers were found stacked one on top of the other, with the lowest placed on ring-shaped stands.

Two large earthen jars, which contained burial urns with several uncalcined human bones in crucible-shaped terracotta reliquaries, were also discovered. Many large burial jars containing uncalcined human bones too big to fit inside the smaller burial urns were similarly unearthed.

Banerjee had no doubt that this chamber was part of the Buddhist monastery. What baffled him was the presence of Indus pots with pointed ends (which he identified as burial urns, though Marshall claimed they were drinking goblets) inside a small chamber of the monastery. Were the Buddhist monks preserving these Indus pots? How could layers of Indus pots and debris be found in a small chamber of the monastery with an open doorway that was never walled up?

To explain this, Marshall suggested that the chamber likely had a staircase ascending to the second storey, and the space beneath it was filled with debris from the Indus ruins, which might have contained these pots. If not this, then there is no other possible explanation, and the matter is best left as an unsolved riddle.

Marshall further added that no such example of a burial chamber inside a Buddhist monastery is known, and it is highly unlikely that such a chamber would be made amid the living quarters of the monks.

In Chamber 27, Banerji discovered a large earthen jar partially buried under the Buddhist brick floor, its mouth covered by a sandstone slab. Inside the jar were small vessels with pointed ends, similar to those found in Chamber 22, which Banerji identified as burial urns. These were embedded in gluey soil mixed with bone fragments. Some bones were placed in crude reliquaries and surrounded by miniature pottery.

Additionally, another large vessel was found beneath the foundations of Chamber 39. It contained similar burial urns, flint scrapers, copper ornaments, and uncalcined bones.

The Presence of Kushan Era Coins

The findings included 1,684 square-shaped coins found in an earthenware pot beneath the second floor in Room 34, and an additional 76 coins in Chamber 35. In total, over 2000 coins were discovered throughout the monastery.

These coins predominantly dated back to the time of Vasudeva I, a Kushan king who ruled between 185-220 AD. However, some coins, identified as fire altar coins, and the presence of certain symbols suggested the area continued to be in use in the later centuries, possibly into the 5th century AD.

A Ziggurat

A ziggurat is a large, pyramidal, stepped religious monument from ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), believed to house a god or gods in the temple at its summit. These structures were part of temple complexes, not open to the public, where only priests were allowed to perform rituals on behalf of the city’s patron deity. The ziggurats symbolized the connection between heaven and earth, with their elevated platforms and sacred temples.

Ziggurats first appeared during the Sumerian Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE) and became prominent architectural features in major Mesopotamian cities. Although their origins date back earlier, most surviving ziggurats were constructed between approximately 2200 and 500 BCE.

Built with a mud brick core and baked brick exterior, they had no internal chambers and were usually square or rectangular, averaging 170 feet square or 125 x 170 feet at the base. About 25 ziggurats are known, located in Sumer, Babylonia, and Assyria.

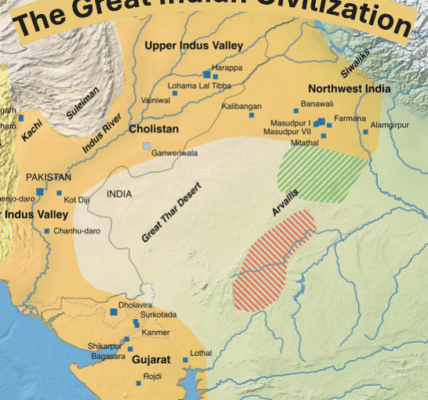

Indus-Mesopotamia Relations

The Indus and Mesopotamian cultures had connections, mainly through trade, during the Bronze Age (around 3300 to 1300 BCE). Archaeological evidence, such as seals, pottery, and goods found in both regions, suggests active trade links. For example, Indus Valley seals have been found in Mesopotamia, and Mesopotamian texts mention trade with a region called “Meluhha,” which is believed to refer to the Indus Valley. While they were economically connected, the two civilizations remained distinct in terms of language, architecture, and religious practices.

An Indus Temple

Long before Sir John Marshall published his report on Mohenjo-Daro in 1931, Rakhal Das Banerji, the person who discovered and first excavated the stupa site, had already submitted a report on his findings in 1926.

But his report was never published.

Mohenjo Daro: A forgotten Report

According to the publisher’s note in Mohenjo Daro: A Forgotten Report, despite submitting a detailed account of his excavations and findings, complete with illustrations and photographs, Marshall kept Banerji’s report to himself. He only returned a typed copy, without the photographs, and that too after four years, in 1930. Marshall claimed Banerji’s report was full of mistakes and irrelevancies while his theories were untenable and incorrect; therefore, he would not publish it.

Marshall suggested that Banerji publish his report separately before he published his own, but he did not return the original report and photographs despite Banerji’s repeated requests. With limited printing facilities at that time and much time wasted requesting the return of his original report and photographs, Banerji was unable to publish his findings, which allowed Marshall to release his own report—the first ever on Mohenjo Daro—in 1931.

It wasn’t until 1984 that Banerji’s report finally saw the light of day, but it was in such bad shape that most of the text was illegible. It remains unknown whether this was how the report was returned to Banerji.

Rakhal Das Banerji

Rakhal Das Banerji was the Superintendent of the Western Circle (Western India) for the Archaeological Survey of India from 1917 to 1924.

Between 1917 and 1920, Banerji actively explored the villages around Mohenjo-daro, gathering details from locals without modern facilities and relying on walking and cart travel. His sociable nature helped him gain vital information about ancient mounds. The stupa site and the surrounding quadrangle were almost entirely excavated by Banerji and his team during the 1922-23 excavation season.

However, Banerji also spent an extensive amount of time surveying the dried-up river channels of the Sutlej and Indus in South Punjab, Bikaner, Bahawalpur, and Sindh from 1918 to 1922. He identified 17 ancient beds of the Indus and the remains of 27 major towns and 53 smaller ones.

Banerji was ahead of his time; he imagined the topography of Mohenjo Daro as it might have been approximately 5,000 years ago based on his research of the dried-up river channels in the region.

A Shrine From Indus Times

Banerji argued that in ancient Sindh, large towns could only have existed along riverbanks, and 5,000 years ago, Mohenjo Daro was located on the southern banks of one of the earliest beds of the Indus River. He noted that remnants of this ancient riverbed were found not far from the city’s ruins.

Within the city itself, there were islands, both large and small, near the river’s southern bank, which the inhabitants used to build temples and shrines. Banerji identified three key islands that were home to such sacred structures, including the site where the hollow stupa now stands.

He proposed that this stupa site originally hosted an Indus-period shrine or temple, strategically placed on a small island near the riverbank. The original shrine was intentionally built at a higher level (relatively lower than the current height) to protect it from the severe floods that frequently plagued Sindh.

Banerji drew comparisons to other island-based shrines in Sindh, such as Khwaja Khizr, Sadh Belo, and Satiyan Jo Asthan—all situated on islands near Mohenjo Daro—proposing a continuity in an ancient tradition of building shrines on islands.

In his report, Banerji noted that the paved courtyard and the quadrangle of rooms encircling the hollow stupa belong to the Indus period, while the hollow stupa itself, along with the platform of burnt bricks upon which it stands, were later constructions. The misalignment between the platform and the hollow stupa suggests that the platform was originally intended for a different, older structure. The hollow stupa, added much later—around the 1st century BC or AD—was not part of the original design.

According to Banerji, an earlier shrine stood on this site at a relatively lower height but was destroyed by a major conflagration, evidenced by the significant ash deposits found during excavations. The brick platform was likely constructed afterward, and the great height of the platform was a result of accumulated debris from successive periods.

Banerji further argued that the rooms surrounding the quadrangle were initially used as shrines rather than living quarters. The presence of an E-shaped platform in one of these shrines indicates the practice of libation rituals, and the discovery of numerous oblation tables and libation cups further underscores the spiritual significance of this site during the Indus period, he added.

Conclusion

The general consensus among scholars, including the late Dr. Michael Jansen—who worked on UNESCO’s “Save Mohenjo Daro” campaign for three decades in Pakistan and studied the monument closely—is that the evidence for the structure being a stupa is quite slim. Jansen called for a careful restudy of the monument, and hoped to excavate at the site but unfortunately passed away in 2022.

John Marshall, then Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India, appeared to be under some pressure or compulsion to label the structure as a Buddhist Stupa, despite numerous inconsistencies that were difficult to ignore and for which he offered no explanation. Strikingly, he never even speculated about the possibility that it could be an Indus-era monument built for a different purpose.

Whether it was a ziggurat, or an ancient Indus temple situated on an island as proposed by R.D. Banerjee, readers are free to draw their own conclusions based on the information provided in the article.

References:

Marshall, J. (1931). Mohenjo-daro and the Indus civilization. Arthur Probsthain.

Banerji, R. D. (1984). Mohenjo Daro: A Forgotten Report. Prithvi Prakashan.

Jansen, M. (2008). Buddhist stupa or Indus temple? Science, 320(5881), p.1280.