The Indus Valley Civilization, also known as the the Indus-Sarasvati Civilization, is the oldest civilization in India.

No one knows for certain where and when this civilization started. Previously, Mehargarh was deemed the most ancient site until carbon dating revealed Bhirrana in Haryana, India, to be the oldest Indus Civilization site (7570-6200 BC), 1,000 to 1,500 years older than Mehargarh.

The Indus Valley civilization was active in the Indian subcontinent from approximately 8,000 BC to 1,500 BC. Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, two big cities of this ancient civilization of India, unfortunately, fell victim to the partition of India in 1947 and now lie within the political territory of Pakistan.

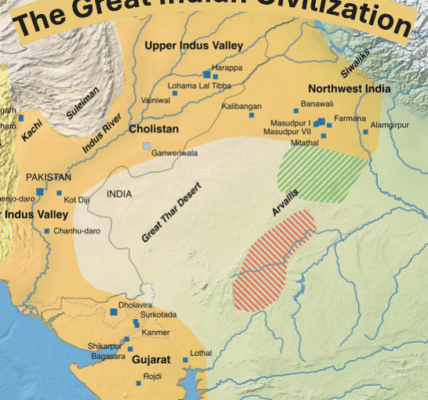

Extent of the Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization extended from present-day northeastern Afghanistan to Pakistan and northwestern India, with an area of around 1.25 million square kilometers. It was one of the most widespread ancient civilizations, spanning an area larger than ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia combined.

Major Sites

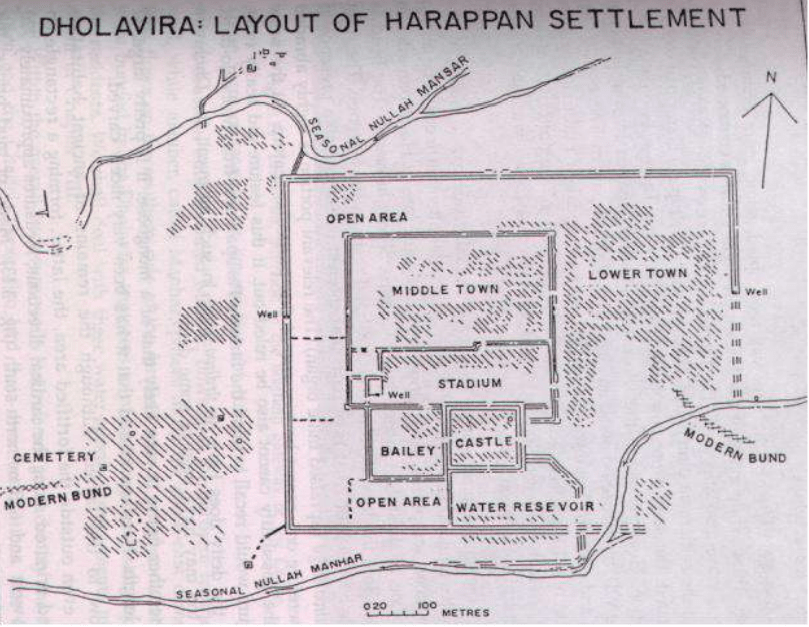

Some of the major sites of the Indus Valley Civilization include Harappa, Mohenjo Daro, Dholavira, Lothal, Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Banawali, and Ganeriwala.

The Design of The Indus Cities

The cities of the Indus civilization were designed according to a grid structure and town planning principles.

Mohenjo Daro was surrounded by massive walls and gateways. These may have been built to control trade, military invasions, and to protect the city from floods.

Each city was divided into two (or three) parts: Citadel (Upper town), lower town, and sometimes there was a middle town as in the case of Dholavira.

In one part, there was a high fort where the rulers lived. In another part of the city lived the governed and the poor. Each part of the city was made of a boundary wall. Each section of each part contained various buildings such as public buildings, homes, markets, art and craft workshops, etc.

The roads were made at right angles, and baked bricks were used in the construction of houses.

The Indus Cities Advanced Drainage System

The drainage system was one of the most remarkable features of the Indus cities. All the surrounding roads and streets had drains, mostly covered and hidden underground.

All houses had drains that were connected to the wide public drains built along the main roads, with holes at regular intervals for cleaning and inspection.

The road drains were made of baked bricks with specially shaped bricks for making corners, laid finely and sealed with a mud layer.

The small drains(from households) channeled wastewater into slightly larger ones. These larger drains would empty into even bigger ones, running along major streets. These bigger drains would handle wastewater from a larger area. Finally, the system culminated in vast sewers – the largest drains that collected wastewater from the entire city where it was disposed of in cesspits or various types of ponds.

Architecture of the Indus Cities

The Great Bath, found at Mohenjo Daro, stands out as one of the most remarkable structures of its time.

Constructed entirely of burnt bricks, this extraordinary bath measures 12 meters in length, 7 meters in width, and reaches a depth of 2.5 meters. Its floor and walls are waterproofed with gypsum and bitumen, showcasing advanced engineering techniques.

Remarkably, during its era, there existed no comparable structure elsewhere in the ancient world.

At Harappa stands the impressive Great Granary.

This vast structure measures 55 meters by 45 meters, comprising two interconnected sections linked by a tunnel. Each section features six storage rooms, each 15 meters long and 6 meters wide. Additionally, air ducts beneath the wooden floor likely served as ventilation channels.

However, it’s worth noting that while the Great Granary is considered a significant architectural feat, some scholars argue that evidence supporting large-scale granaries at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa is scant, suggesting that these structures may have served primarily as large public buildings.

The Indus Valley Civilization city of Dholavira had a sophisticated water management system unmatched in the ancient world. This network included water reservoirs, canals, and wells, all constructed from stone. Dholavira had least sixteen water reservoirs, one of which discovered in 2014 (pictured above), is three times larger than the Great Bath at Mohenjo Daro.

Arts and Crafts of the Indus People

Excavations of Indus cities have yielded many evidences of artistic activity. The popular art of the Indus civilization was in the form of terracotta figurines.

Most of them are females, often laden with ornaments, but males, some with beards and some with horns, are also present.

The art of pottery making was at its zenith in the Indus Valley Civilization. The Indus potter was a skilled craftsman who produced plain, colored, and glazed pottery. There is also a small but notable display of bronze sculptures including fragments and complete examples of dancing girls, miniature chariots, carts and animals.

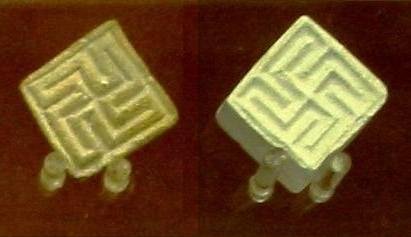

The Indus Seals

The most renowned relics of the Indus Valley Civilization are its seals, which feature various motifs such as single-horned creatures like unicorns or bulls, Indian humped bulls, elephants, bison, tigers, and deities of the era. These seals often depict intricate scenes and symbols, providing valuable insights into the civilization’s religious beliefs and cultural practices.

Additionally, the Indus Valley script, found on these seals and other artifacts, remains undeciphered to this day. As a result, many aspects of the civilization’s language and writing system remain enigmatic, posing a challenge to scholars and historians in understanding the full extent of their communication and record-keeping practices.

Occupation of the Indus People: The First Farmers and Traders

The residents of Indus Valley Civilization were primarily farmers. A research conducted by the Department of Archaeology of the University of Cambridge in 2016 confirmed that the farmers of the Indus civilization were the first people to use multi cropping strategies in both seasons. They grew rice, millet and beans during the summer and wheat, barley and pulses in the winter, which have distinct irrigation requirements. A network of farmers then took their produce to the markets of all the ancient cities.

The Indus civilization was an agricultural society, but trade was equally important. To facilitate trade, they utilized bullock carts and boats, potentially being among the earliest users of wheeled transport, as evidenced by the continued presence of bullock carts in South Asia today.

Additionally, the people of the Indus civilization were adept sailors, constructing boats and kayaks for maritime activities. In particular, the city of Lothal has been identified as a coastal hub where these vessels were docked.

Traders from the Indus Valley civilization engaged in extensive maritime trade, venturing across bodies of water like the Arabian Sea, the Red Sea, and the Persian Gulf. Their trade network facilitated the import of various raw materials crucial for the workshops of their cities. These materials included minerals sourced from regions like Iran and Afghanistan, as well as lead and copper from different parts of India.

Furthermore, luxury items were also traded, with jade imported from China and cedar wood transported down rivers from the Himalayas and Kashmir. Other trade goods included terracotta ware, precious metals like gold and silver, various metals, flint for tool making, decorative stones, conch shells, and colored gems such as lapis lazuli and turquoise, sourced both from distant lands and other regions within India.

There was an extensive maritime trade network between the Indus Civilization and Mesopotamia. Indus seals and jewellery have been found at archaeological sites in areas of Mesopotamia that include parts of modern Iraq, Kuwait, and Syria.

Religion of the Indus Valley Civilization People

The religious practices of the Indus people are considered to be ancestral to, or at least one of the ancestors of, the present-day Hindu religion.

No definitive religious sites have been unearthed in Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, but this absence doesn’t negate the likelihood of religious practices. Scholars suggest that the inhabitants of these cities worshipped what is called the Mother Goddess. Shakti, representing the female cosmic energy, is still worshipped in contemporary India.

Similarly, alongside the Mother Goddess, a male deity resembling an early form of the Hindu god Shiva was worshipped. Lingam structures discovered in Mohenjo Daro and Harappa are interpreted as representations of the Shiva-Linga, with the Yoni rings serving as symbols of Shakti, the female cosmic energy.

A seal called the Pashupati Seal, found at Mohenjo Daro, is widely accepted as one of the earliest representations of Lord Shiva (pictured above). Scholars also believe that the three horns of this deity later evolved into the trident of Shiva.

Apart from this, the bull and the peepal tree was considered sacred by the Indus people, just like by today’s Hindus.

Seals depicting Swastikas have also been found at Mohenjo Daro, Harappa, and Dholavira.

As no evidence of fire rituals was found at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, historians and archaeologists concluded that the Vedic religion came from outside India, and later merged with the Indus religion, giving rise to what we now recognize as Hinduism in India.

However, the discovery and excavation of Indus civilization sites in India have challenged this perspective. The unearthing of fire altars at Kalibangan has raised doubts about this theory. Many scholars now agree that these fire altars provide evidence of fire rituals being practiced during the time of the Indus Valley Civilization.

Disposal of the Dead in the Indus Valley Civilization

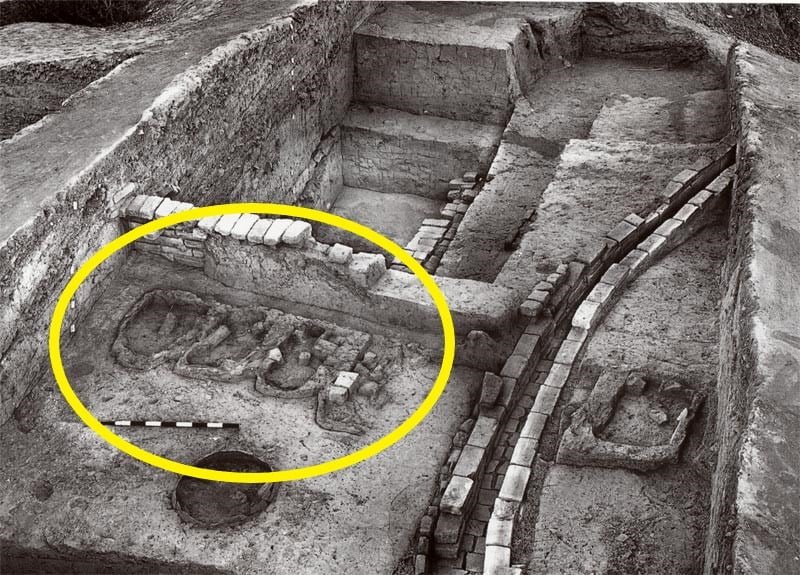

Archaeological excavations at sites like Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa, Lothal, Dholavira, and others have provided invaluable insights into the diverse funerary practices of the Indus Valley Civilization.

Within the Indus Valley civilization, there were four ways of disposing of the bodies of the deceased:

- Complete Burial within graves or burial pits.

- Complete Cremation. The ashes were then likely either interred or scattered.

- Partial Burial where only the bones of the deceased were buried, either in burial jars or directly in the ground.

- Post Cremation Burials where the remains, often reduced to ashes, were placed in large burial pots or vessels.

Sometimes bones of more than one person were found in a burial jar. The most common form of disposing of the dead was Post Cremation Burial. Post cremation burial pots belonging to all phases of the civilization have been found buried under streets and buildings of Mohenjo Daro and Harappa.

By 1931, only 21 skeletons were found at Mohenjo Daro. Most of them appear to have been victims of some sort of accident, who were buried at those sites after the end of the Indus civilization.

In contrast, about 90 skeletons were found at Harappa, of which only 19 were complete. In a cemetery called R 37, some skeletons were in wooden coffins. Most of the skeletons were accompanied by gold and semi precious stones, pottery, conch shell bangles and steatite beads. This suggests that these individuals buried in the cemetery represented an upper class of the city.

At least 126 large post cremation burial pots have been found at Harappa containing small vases, bones of small four legged animals, birds or fish, shell bangles, beads and terracotta figurines mixed with ash and charcoal. Only one of the 126 had some human bones. From this it was inferred that after cremation, the human bones were either:

- Dispersed into a river and the remaining ashes buried with the pot.

- After cremation there were no bones left, therefore only ashes were buried.

- Human bones were probably crushed and mixed with the ashes.

A post cremation burial pot usually contained ash, traces of charcoal, terracotta figurines of animals, men or women, dog, goat, or ram bones, shell bangles, steatite beads, and pieces of jewellery.

In summary, how the Indus Valley Civilization people disposed their dead gives us a glimpse into the beliefs and customs of one of humanity’s oldest city-based societies.

Other Notable Information

- The Indus Valley people had a sophisticated system of weights and measures, suggesting a well-developed trade network.

- The Indus Valley people valued peace over warfare. This is based on the lack of weapons and fortifications found in their cities, peaceful imagery in their art, and a focus on urban planning for a comfortable life.

- The decline of the Indus Valley Civilization around 1900 BCE is attributed to various factors, including climate change, environmental degradation, and the drying up of the Sarasvati River.

Reference List:

1. Marshall, J. (1931). Mohenjo-daro and the Indus civilization. Arthur Probsthain.

2. Vats, M.S. (1940). Excavations at Harappa (Vol. I & II). Delhi: Government of India Press, Archaeological Survey of India.

3. Wheeler, M. (1953). The Indus Civilization. Cambridge University Press.

4. Haryana’s Bhirrana oldest Harappan site; Rahkigarhi Asia’s largest

5. Bates, J., Petrie, C. A., & Singh, R. N. (2017). Approaching rice domestication in South Asia: New evidence from Indus settlements in northern India. Journal of Archaeological Science, 78, 193-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.04.018

6. Roots Of Vedic Rituals: On Harappan Fire Worship And It’s Vedic Parallels