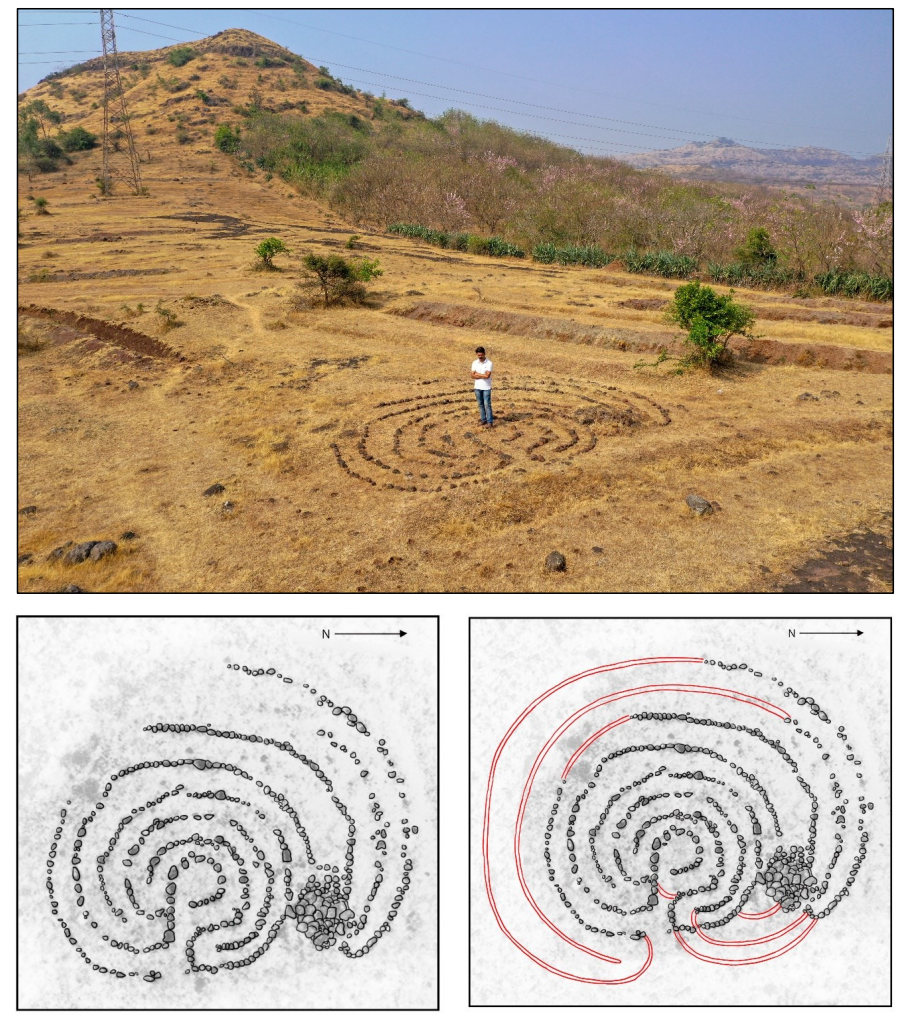

India’s largest newly discovered circular stone labyrinth, the Boramani stone labyrinth, sits in the Boramani grasslands of Solapur district in Maharashtra. A conservation patrol spotted the near-perfect stone ring while monitoring wildlife in the grassland safari landscape. Field teams tracking the Great Indian Bustard and predators such as wolves noticed the deliberate circular formation. Archaeologists later inspected the site and confirmed its scale. The Boramani stone labyrinth measures roughly 50 feet by 50 feet (about 15 m by 15 m) and runs through 15 concentric circuits that lead to a tight central spiral.

Reports describe it as the largest circular stone labyrinth recorded in India so far. It stands out for its complexity too. Many earlier circular examples in India show about 11 circuits, while Boramani has 15. A well-known square stone labyrinth at Gedimedu in Tamil Nadu is larger in overall area at about 56 feet by 56 feet (about 17 m by 17 m), but Boramani holds the record for a circular layout and for the highest circuit count.

Labyrinth historian Jeff Saward places the Boramani design within the classical family of labyrinth layouts. He also highlights a detail that links the form to Indian naming. The centre spiral is strongly associated with India and many writers describe it as chakravyuh, a term remembered from epic tradition.

Ancient Trade Routes and Indo-Roman Exchange

If reports are to go by, archaeologists date the Boramani stone labyrinth to the Satavahana period, roughly from the late 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE. During this era, inland roads tied much of the Deccan to western ports, and the Satavahana age overlaps with what scholars describe as Indo-Roman trade. Roman coin finds in India are often cited as a quick marker of this long-distance exchange.

The design of the Boramani stone labyrinth belongs to a recognisable labyrinth tradition, and similar labyrinth motifs appear on coins and artworks from the Mediterranean world, including imagery associated with Crete and Roman-era mosaics.

The wider Maharashtra labyrinth belt

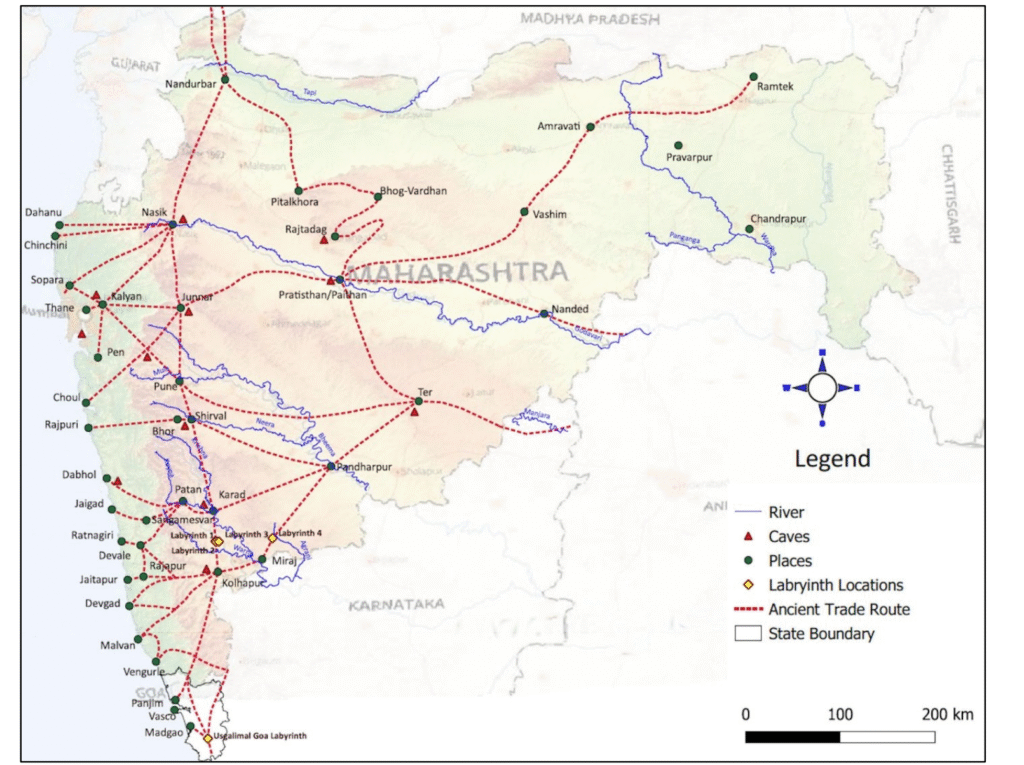

Boramani’s scale is headline-making, but it fits into a broader pattern across Maharashtra. Archaeological documentation from western Maharashtra, especially Sangli district, records several stone labyrinths built in the classical seven-circuit form. Notable examples include two labyrinths at Aitawade Budrukh, measuring about 38.4 feet and 30.2 feet in diameter (11.7 m and 9.2 m). Researchers also recorded a damaged but reconstructable labyrinth at Vashi, set in a pass between hillocks. Another example at Malangaon now sits inside a protective enclosure.

What makes these Maharashtra examples especially interesting is their location. Researchers note that several stone labyrinths sit near route splits, passes, and junctions that connect early historic centres such as Kolhapur, Karad, and Ter. This placement suggests a practical role. The labyrinths could have served as memorable landmarks for travellers moving along busy corridors. At the same time, people could have read them as ritual or symbolic designs. In that light, Boramani looks less like a random oddity and more like the largest surviving expression of a landscape practice already present in the region.

Labyrinths elsewhere in India

Image credit: Clayton Lobo (Google)

Maharashtra is not the only region with stone labyrinth traditions. Tamil Nadu has the best-known large built example, the Gedimedu square labyrinth. It is known not only for its size but also for local belief. Reports quote researcher S. Ravikumar saying that tradition links the site to wish-fulfilment for those who walk the route correctly.

Tamil Nadu also features circular discoveries. Researchers have reported a circular stone labyrinth near Hosur in Krishnagiri district and linked it to an early date, around 2,500 years old. Together, Gedimedu and Hosur show that India used more than one shape and more than one setting for these designs.

Labyrinth motifs also appear beyond ground-built structures. Rock art sites include labyrinth-like carvings in petroglyph contexts, including a prominent example at Usgalimal in Goa’s Kushavati river landscape. Researchers connect the carving to the wider prehistoric engraving tradition there and discuss possible ritual significance. Academic studies that survey labyrinth motifs in Indian rock art treat these designs as part of a wider symbolic vocabulary, not a one-region curiosity.

Labyrinths outside India

Across cultures, people treat labyrinths as guided journeys, not puzzles. A maze forces choices. A labyrinth usually gives one path. The route winds inward to a centre, then leads back out. With no decision points, the walk builds rhythm. Many traditions link it to endurance, transition, and renewal.

In Europe and the Mediterranean, the design shows up in many settings and carries layered meaning. Greek tradition ties it to Crete through the Theseus story. Roman artists later turned it into a strong symbol, especially in mosaics. In that art, it can suggest danger overcome or a hard trial completed. Medieval builders also placed labyrinths on church floors. Worshippers then walked them as symbolic pilgrimages. Modern designers revived the same single-path form in parks, hospitals, and wellness spaces. Today, people walk for calm and focus.

Source: Riksantikvarieämbetet / Bengt A Lundberg, CC-BY, CC BY 2.5 SE https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/se/deed.en, via Wikimedia Commons

Beyond Europe, the idea appears in several regions in different forms. Ancient writers also describe the Egyptian “Labyrinth” at Hawara as a vast, maze-like monument. In North America, Indigenous traditions use the “Man in the Maze” symbol to express life’s journey. In the Near East, researchers discuss large concentric “wheel” monuments that some compare to labyrinth forms.

Meaning of labyrinths in Ancient India

Figure 9. Carving showing the warrior Abhimanyu entering the chakravyuh – Hoysaleswara temple, Halebidu, Karnataka, India. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In ancient India, labyrinth-like designs carried their own local names and meanings. Across the subcontinent, these forms appear in different contexts, from stone layouts in the landscape to motifs in art and living traditions.

One common label for such patterns is chakravyuh. In the Mahabharata, it is shown as a multi-layered battle formation, arranged like a wheel or spiral, where entry was possible but escape was extremely difficult. The epic’s famous episode involves Abhimanyu, who knows how to break into the chakravyuh but is cut off inside and cannot find a way back out, a scene often depicted in temple art

Interpretive writing also uses manaschakra, described as a symbol linked with personal and spiritual growth. Another term sometimes applied is yamadwara, understood as a symbolic threshold tied to passage and transition.

These ideas sit alongside everyday traditions where people actively create and understand labyrinth-like geometry. Rangoli, for example, often uses concentric or pathway-like patterns at entrances and ritual spaces, where the design signals auspiciousness and meaning. Seen through this wider Indian lens, large stone labyrinths such as Boramani can read as public-facing markers in the landscape, combining movement, memory, and symbolism. The continued presence of such forms strengthens a simple point about ancient India: ancient Indians shaped meaning not only through cities and shrines, but also by laying deliberate patterns into open terrain.

Boramani is the clearest reminder yet that India’s labyrinth tradition still has discoveries waiting in open landscapes.

Sources:

- Times of India. (2025, December 22). India’s largest circular labyrinth unearthed in Maharashtra’s Boramani grasslands; what we know so far. Times of India. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/travel/indias-largest-circular-labyrinth-unearthed-in-maharashtras-boramani-grasslands-what-we-know-so-far/articleshow/126092661.cms

- Times of India. (2025, December 19). India’s largest circular labyrinth discovered in Solapur’s Boramani grasslands. Times of India. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolhapur/indias-largest-circular-labyrinth-discovered-in-solapurs-boramani-grasslands/articleshow/126063526.cms

- India Today. (2025, December 22). Boramani stone labyrinth in Maharashtra linked to Satavahana era and Indo-Roman trade. India Today. Retrieved from https://www.indiatoday.in/science/story/boramani-stone-labyrinth-maharashtra-satavahana-indo-roman-trade-2839744-2025-12-22

- MSN. (n.d.). From Maharashtra to Rome: 2,000-year-old labyrinth reveals trade route lost in time. MSN. Retrieved from https://www.msn.com/en-in/travel/news/from-maharashtra-to-rome-2-000-year-old-labyrinth-reveals-trade-route-lost-in-time/ar-AA1SOnrj

- Patil, S. B., & Sabale, P. D. (2021). New discovery of stone labyrinths in Western Maharashtra, India. Caerdroia, 50. Retrieved from https://labyrinthos.net/C50%20Stone%20Labyrinths%20Maharashtra.pdf

- Saward, J. (n.d.). Historical overview. The Labyrinth Society. Retrieved from https://labyrinthsociety.org/historical-overview/

- Ashmolean Museum. (n.d.). Myths of the labyrinth. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. Retrieved from https://www.ashmolean.org/article/myths-of-the-labyrinth

- Roman Provincial Coinage Online. (n.d.). What is RPC? University of Oxford. Retrieved from https://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/introduction/whatisrpc

- Kumar, A. (2015). Labyrinths in rock art: Morphology and meaning with special reference to India. Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology, 3. Retrieved from https://www.heritageuniversityofkerala.com/JournalPDF/Volume3/6.pdf

- Goa Prehistory. (2019). Rock-art at Usgalimal, Goa: A Neolithic open museum (overview). Retrieved from https://goaprehistory.files.wordpress.com/2019/06/rock-carvings-in-usgalimal.-an-overview.pdf

- Times of India. (2015, August 4). Second largest maze of ancient stones found. Times of India. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/second-largest-maze-of-ancient-stones-found/articleshow/48336948.cms

- Times of India. (2018, April 10). A rare circular labyrinth discovered near Hosur. Times of India. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/a-rare-circular-labyrinth-discovered-near-hosur/articleshow/63687612.cms

- Navigating the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. (n.d.). Paithana (Periplus ch. 51 context). Retrieved from https://navigating-the-periplus.github.io/locations/paithana.html

- Caerdroia – the Journal of Mazes & Labyrinths: https://labyrinthos.net/caerdroia.html